Our guest today is Vijay Raina, a leading specialist in enterprise SaaS technology whose thought leadership is shaping conversations around software architecture in the age of AI. We’re here to discuss a seismic shift on the horizon—a potential $500 billion collapse in the enterprise software market, driven by the very AI that was supposed to be its next great evolution.

Some analyses suggest AI could put $500 billion in enterprise software revenue at risk by shifting work from humans to autonomous agents. What specific workflows are being automated this way, and how does this make traditional software interfaces redundant? Please share a concrete example.

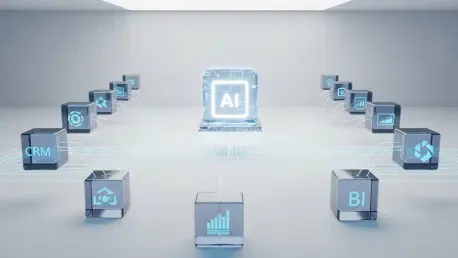

It’s a fundamental rewiring of how work gets done. For decades, software was built to augment a human. Now, AI agents are beginning to replace the human-software combination entirely. We’re seeing this in complex, multi-step processes that used to require a person to toggle between five different applications. Imagine a sales operations task: a human receives an email from a client, opens the CRM to update the contact record, switches to a BI tool to pull a sales history report, and then opens a project management app to create a new task for the account manager. An AI agent can now do all of that autonomously in the background. It reads the email, accesses the databases of those different applications via their APIs, and executes the entire workflow in seconds. In that scenario, the graphical user interfaces of the CRM, BI tool, and project manager become completely unnecessary. The software’s value proposition as a human-centric tool just evaporates.

The per-seat subscription model has been the backbone of SaaS. With one AI agent potentially doing the work of ten employees, how does this economic model break down? What are the biggest risks companies face when transitioning to consumption-based or outcome-based pricing models?

The per-seat model is facing an existential crisis. Its logic is simple: more human users equals more revenue. But when a single AI agent can do the work of ten, or even a hundred, employees, that entire equation collapses. You can’t charge for ten seats when only one non-human agent is doing the work. The biggest risk in shifting away from this model is the loss of predictability. Investors, both public and private, fell in love with SaaS because of its predictable, recurring revenue. It was a golden goose. Moving to a consumption or outcome-based model introduces volatility. Your revenue could swing wildly based on usage, which is much harder to forecast. This transition is incredibly fraught with peril; it could completely devastate the financial profiles that made these companies Wall Street darlings in the first place. They risk trading a stable, high-margin business for an unpredictable and potentially lower-margin one.

Categories like help desk support, basic data analytics, and even Robotic Process Automation appear highly vulnerable. What makes these specific software types prime targets for disruption, and what unique capabilities allow new AI-native systems to completely replace them rather than just improve them?

These categories share a common vulnerability: they primarily act as an interface layer between a human and a system of record or data. Help desk platforms are a classic example; they help a support agent access information to answer a customer’s question. An AI agent can now access that same information and communicate with the customer directly, making the human-facing platform redundant. The irony with Robotic Process Automation, or RPA, is palpable. Companies like UiPath built enormous businesses by creating bots that mimicked human clicks on a screen. But that approach is incredibly brittle; if the user interface changes, the bot breaks. AI agents are fundamentally different. They don’t mimic clicks; they interact with systems intelligently through APIs, understand context, and can adapt on the fly. They aren’t just improving the old process; they are replacing it with something far more efficient and robust.

Established giants like Microsoft and Salesforce face an innovator’s dilemmcannibalize their own products with AI or be displaced. How is this challenge playing out in their current strategies, and what practical steps must they take to evolve from a software provider to an essential AI orchestration layer?

This is the billion-dollar question keeping executives in Silicon Valley up at night. You see it playing out in real-time. Microsoft has been incredibly aggressive, weaving its Copilot assistant into the entire Office 365 suite and charging a premium for it. However, they face the tricky internal question of what happens when a single Copilot command can perform a task that previously required licenses for three different products. They are walking a tightrope. Salesforce is making a similar bet with its “Agentforce” platform, explicitly trying to rebrand from a CRM provider to an “AI agent orchestration layer.” The challenge for them is immense. The bulk of their revenue comes from the traditional CRM interface. If AI agents can manage customer relationships autonomously, that core product could become an afterthought. To survive, these giants must ensure their platforms become the indispensable substrate—the foundational layer—on which all these AI agents operate. If they fail, they risk being bypassed entirely.

New startups are building API-first systems assuming AI agents, not humans, are the primary users. How does this design philosophy differ from traditional software development? Could you walk us through how an AI-native product would handle a task like generating a quarterly sales report?

The design philosophy is a complete one-eighty. For twenty years, software was built around the graphical user interface, or GUI. The primary concern was making it intuitive and easy for a human to use. In an AI-native, API-first world, the GUI is an optional layer, not the core product. The core product is a clean, powerful, well-documented API designed for a machine to consume. To generate a quarterly sales report, the old way involved a human opening a BI tool, dragging and dropping fields, setting filters, and exporting the data. In an AI-native system, a business leader would simply say or type, “Generate the Q3 sales report, highlighting top-performing regions and products.” An AI agent would interpret that command, make dozens of API calls to various databases for sales figures, customer data, and product information, synthesize the insights, generate the full report with visualizations, and distribute it—all without a single human logging into a dashboard. The software is built for the agent, not the person.

The disruption in software is directly tied to changes in workforce strategy. As companies deploy AI agents, how does this impact their software budgets and their headcount in areas like customer support? What cascading effects should business leaders anticipate across their organizations?

The two trends are inextricably linked. When a company decides to deploy AI agents to handle 80% of its customer support inquiries, it isn’t just a technology decision; it’s a workforce and budget decision. They don’t just cancel their per-seat help desk software subscription for hundreds of agents; they also reduce their customer support headcount. This creates a powerful cascading effect. For decades, enterprise software budgets have been on a relentless upward climb. We could now be looking at a future where those budgets plateau or even decline because companies find they can achieve more with a handful of powerful AI agents than they could with thousands of employees using dozens of different software tools. Business leaders need to anticipate that this isn’t just about saving on software licenses; it’s a fundamental rethinking of their entire operational cost structure, from personnel to the very tools they use.

Investors are now distinguishing between vulnerable software companies and those with more defensible positions. What defines a “data moat” or an “infrastructure-layer” company in the AI era, and why are these businesses considered safer investments? Please provide some specific metrics to watch for.

The smart money is getting very discerning. A “data moat” refers to a company that possesses a massive, proprietary dataset that is essential for training or operating effective AI agents in a specific domain. An AI is only as good as the data it’s trained on, so owning a unique and valuable dataset creates a powerful competitive advantage. An “infrastructure-layer” company provides the fundamental building blocks that everything else runs on. Think of cloud platforms, data pipelines, or identity management systems. These are considered safer because no matter which AI application or agent wins, they will all need these foundational services to function. Investors are looking for companies whose value isn’t tied to a specific human-facing interface but to the underlying data or infrastructure. The metrics to watch are shifting from user engagement on an app to things like API call volume, the amount of data processed, and the ecosystem of AI agents being built on top of their platform.

What is your forecast for the enterprise software industry over the next five years?

The next five years will be a period of intense, chaotic, and transformative change. I believe the analysis pointing to a great reckoning is largely correct. We will see entire product categories that are mainstays today, particularly those acting as simple interfaces for knowledge workers, become obsolete. The transition will be brutal for incumbents who are slow to reinvent their core business models away from per-seat licenses. However, this creative destruction will also fuel a massive wave of innovation, giving rise to a new generation of AI-native companies built on entirely new principles. The most successful companies will be those that become essential infrastructure for an AI-driven enterprise. The software industry isn’t dying, but it’s being reborn into something unrecognizable from what we’ve known for the past twenty years.